Text by Carl Oechsner

Photographs by Howie Myers

Cemeteries are a record of our nation’s past. There is a rich collection of history located on their grounds. Here in our village we are fortunate to have fantastic examples of period gravestones dating back to the 1700s. Bethel Cemetery is a most charming space, located in the virtual center of our community, surrounded by our schools, library and neighborhoods. Residents pass by and through it on a daily basis making it a part of our village.

The following was adapted from a presentation given at the Croton Free Library. We are still researching a number of interesting questions. Are Native Americans and African American slaves buried within the confines of Bethel? Was there ever a Potter’s Field for indigent individuals? Should you have any information, questions or comments regarding Bethel, please contact us. We would love to hear from you.

Gravestones are America’s earliest sculpture. Among early American artifacts they are unique in that each is dated and most are found in their original settings surrounded by similar objects from the same period. The majority of artifacts that have survived 200-300 years—paintings, furniture, silver, quilts, books, pottery, tools, and nearly everything we now have from the Colonial period—have been relocated to museum settings and other collections.

An American colonist, reincarnated and walking through the streets of Croton today, would be hard put to find anything he recognized except the old Village burying ground. There he would see stones he knew, still grouped by family and bearing familiar names and verses.

What is the meaning of the designs carved on gravestones? This question is often asked by both the interested layman and the serious student of gravestone art. A great deal of casual speculation and scholarly research has been devoted to finding answers.

The earliest graves at Bethel were marked with local fieldstones or with wood markers. None has survived so it is impossible to know how many there may have been. Grave markers that followed were made from slate, sandstone, marble, granite, limestone, schist, soapstone, and any other stone that was available. Until transportation by rail became an option, most communities used whatever stone was brought by wagon from the nearest quarry, although villages like Croton, on the banks of the navigable Hudson River, were able to get stone from farther away.

Gravestone carvers practiced their trade for almost 150 years throughout the Colonies. The finest work was completed in New England. Here at Bethel Cemetery we still have wonderful examples of stone work done mostly in the 1800s. There were four major periods of gravestone art in our nation’s history.

1650-1750 Winged skulls with blank staring eyes and a grin. A common epitaph would be “Behold and see as you pass by, as you are now so once was I, as I am now you soon will be, prepare for death and follow me.” Slate, which was soft and easy to carve with a hammer and chisel, was the common stone. Bethel does not have any gravestones carved during this time period.

1750-1800 Winged angels, flower designs and flowing poetry. Red sandstone, mostly carried as ballast on ships plying the Hudson River from the Connecticut River and New Jersey, was used. A few remain here.

1800-1825 By the time these stones were carved, most customers favored granite and marble over sandstone. Here the shape is a plain rectangular tablet, recalling an ancient Greek upright slab or pillar or stone. Memorials became less decorative with emphasis shifting to written inscriptions.

1825-1850 At this time a strong interest in neoclassic art was evident in American architecture, painting and other decorative arts. In cemetery art the change in motifs was striking. The most popular themes became the neoclassic urn and willow which were carved in every conceivable variation with columns, tassels, banners, drapery, and occasional mourning figures weeping over the urns and under the willows.

You would gather with family and friends, pray or just relax by walking among the rows of stones. It was a spot for physical exercise and spiritual instruction during the break between morning and afternoon sermons on Sundays. Ministers enjoyed having the graveyard right outside the chapel. It was a constant reminder to all who came to worship that their day would also come. In a subtle way it may have suggested to the faithful to fear death and make certain to attend services each and every week in order to save their souls.

Bethel Chapel is a rare and unusually intact example of religious architecture from the 1700s. Built a few years after the end of the Revolutionary War, it is the earliest Methodist meetinghouse in Westchester County. Except for its large windows, it looks like a small farmhouse. According to local tradition, Pierre Van Cortlandt donated the land for a church and cemetery to the Methodist Society.

The gates to Bethel Cemetery in the 1800s, located along Old Post Road where the driveway to the chapel is today.

The first record of Bethel Chapel is Freeborn Garretson’s journal for Sunday, March 10, 1793. After staying at the Croton Manor House, Garretson reports, “I preached in the new church to a few.”

Francis Asbury, who became the first bishop of the Methodist Church in America in 1784 and founded the Methodist system of circuit-riding, preached at Bethel in 1795, 1812 and 1817.

The only known image depicting a camp meeting in Croton was published in The Zion Songster: A Collection of Hymns and Spiritual Songs, Generally Sung at Camp and Prayer Meetings, and in Revivals of Religion.

Summer camp meetings for Methodists who lived in the Hudson River Valley were first held in Carmel around 1804. In 1805 Croton Landing became the new site with hundreds of religious enthusiasts attending the week-long summer activities. The campgrounds were located in a “grove” near today’s Carrie E. Tompkins Elementary School with the Chapel being used on a daily basis.

Postcard of the Asbury Methodist Church and Parsonage

The still active cemetery has been the only public burying ground in the Village for over 200 years. The Chapel is still used for weddings, funerals and other special events. After the Civil War, Croton remained a fairly small, rural community, but by 1875 the Methodist congregation had grown enough to justify the construction of a larger church. A site was purchased closer to the center of the Village and the new church was dedicated in 1883. Both Bethel Chapel and the Asbury Methodist Church are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

This is an example of the oldest red sandstone markers in Bethel Cemetery. The rounded shape symbolized the “doorway to heaven” and the “hood of death.” The stones are marvelous testimony to the creative skills of the talented artisans who carved them. Most of the men who cut gravestones were uninstructed craftsmen whose work was largely independent of formal principles of design. They worked alone in small villages, usually having another more profitable occupation such as blacksmithing, farming or fishing, receiving little or no attention for the unique work they did.

Today many states, especially in New England, have passed strict laws that protect these heirlooms. Each year increasing numbers of people venture into cemeteries to research genealogy, take photographs and enjoy the experience.

It is quite possible that this stone was created by an apprentice of John Zuricher, the well-known master stonecutter. Zuricher lived and worked in New York City until the Revolution. About 1776 during the British occupation of the City, he moved to Haverstraw in Rockland County. There is no further evidence of him after 1778.

A gravestone cut by John Zuricher, or one of his apprentices, in the Old Dutch Church cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, N.Y.

Zuricher belonged to and trained a group of closely related New York area stonecutters, all of whom carved in a similar manner. Unfortunately, this stone has been severely weathered over the years. Members of the “Zuricher circle” are especially well represented at the Old Dutch Burying Ground at Sleepy Hollow.

A tree that has been an important part of the lore of the churchyard cemetery is the willow, weeping or otherwise. Its popularity as a symbol of grief made it a very common feature of funeral monuments. Being a water-loving plant, the willow offered considerable practical advantages in draining water from low-lying plots. Its large root system helped to keep the cemetery reasonably dry and cut down on soil erosion around graves. Branches of willows were often carried at local funerals. The willow also offered abundant shade to visiting relatives and friends.

The Gothic Revival period became popular in America around 1840, especially here in the Hudson Valley, with the work of architects like Alexander Jackson Davis, who designed Lyndhurst in Tarrytown. The pointed arch, a major design theme of the period, appeared on numerous gravestones.

The lamb is the most common animal symbol found on a child’s grave. It appears throughout the ages with great regularity in Christian art as a symbol of Christ, signifying His sacrificial role of innocence, meekness, gentleness, purity and humility.

The anchor has always been a sign of hope, safety and security. Christ was the true anchor in the storm of life. Believing in Him was the one sure way to attain heaven. With Croton’s proximity to the Hudson River, it is quite possible that the Lents were involved in some form of river activity.

The rose tells us that our lives consist of budding, blooming and withering. The different stages of a rose indicated the person’s age at time of death. The dove symbolized Christian love, innocence, gentleness and devotion, as well as the flight of the glorified soul to heaven.

The function of the stone was twofold: first, to identify the plot of land where someone was buried and, second, to give basic information—name of the departed, date and place of birth, name of spouse if any, date and place of death, cause of death, occupation. Next came the epitaph which presented a moral quotation meant to influence those left behind. Lastly, the shape, design and carvings were created to impress those viewing the final resting place.

Over time many old stones stand below the intended ground line, lowering their above-ground height and hiding the inscriptions.

Stones and their carvings are being eroded by freezing winters and polluted air, by the mischief of vandals and by lichen, a common fungus that appears on stone surfaces and can spread widely. Many stones have sunk so far into the ground that much of the inscription is no longer visible.

Carvers during the Colonial and Victorian periods often charged by the letter, so the lengthier the inscription the greater investment on the part of the bereaved purchaser. This marker contains only the most minimal information about the deceased and the stone is simply carved. Presumably these kinds of gravestones were less costly.

What is stronger than a mother’s love for her child? At the top of this stone is a scroll which symbolized life and time, along with what may be a garland of flowers telling us that the deceased has passed to eternal life. Here are some typical epitaphs for children from the 1800s:

“A light from our household is gone, a voice we loved is stilled, a place is vacant in our home that never can be filled.”

“Short was my time, the longer my rest, God took me hence as he thought it best.”

“This lovely bud so young, so fair, called home by early doom, just came home to show how sweet a flower in paradise would bloom.”

This is a fine example of a family plot, a creative rough-hewn carving. The significance of cemetery plots is shared by almost all cultures going back thousands of years. For Christians living in Rome, cemeteries served a spiritual function and special ground was set aside as holy just for the burial of remains. Today, cemeteries next to a church continue that tradition.

In ancient cities entire cemeteries would spring up around a site where a Martyr, Saint, or particularly blessed person was buried. The presence of a Martyr to watch over their loved ones gave people comfort and, some hoped, good fortune. Modern standards for burials developed under Henry VII, King of England 1485-1509. Plots were set aside with a carved rock and entombment practices were formalized into our familiar traditions today.

This stone is most interesting because it memorializes a woman as an individual, using her maiden name. When a maiden name was used, it meant that her family was very close to her husband’s relatives. During the Colonial and Victorian periods, women’s names were always attached to a man, if not her husband, then her father. Inscriptions for males rarely mentioned their wives. Should a man die before his wife, a stone was erected for him. After his wife passed away, her stone, always smaller, was erected beside his. On the other hand, when a woman died before her husband, it was not unusual for her to be buried in an unmarked grave. Only after the death of her husband was a stone erected on which her husband’s inscription was carved above hers.

The obelisk is one of the most pervasive of all the Revival forms of cemetery art. There is hardly a cemetery founded from 1800-1850 without some form of Egyptian influence. Napoleon’s 1798-99 Egyptian campaigns, the discoveries at the tombs of the Pharoahs, and the desire of our new Republic to borrow the best from ancient cultures led to a resurgence of interest in ancient Egypt.

This is a metal obelisk which is in a class by itself. Ordered from mail order companies such as Sears & Roebuck, the cast iron had distinct advantages and disadvantages as a material for memorials. On the credit side they afforded durablity, easy and cheap manufacturing, and the freedom to create new designs, which was impossible to do in stone. Disadvantages included the essentially repetitive process of making them, and the difficulty of adding further lettering once the design had been cast.

The panel with the lettering was usually cast by a blacksmith in the local village and then bolted to the surface.

Quite a local mystery here. What happened to the Fowler brothers within a period of only three days? The epitaph seems to imply a deep religious belief on the part of the family.

The most well known and loved of Christian symbols is the simple cross. It is a sign of salvation and hope and Christians believe that it has the power to defend them from evil. It represents Christ’s victory over death and sin. The handmade nature of this cross, using local cobbles, is unusual. At the bottom is etched “Mother.”

This hard-to-find marker, with a plaque that reads “The Grave of John J. Peterson, Revolutionary War, Westchester Militia (1746 – 1850)” is the grave of a little-known African American soldier, who played a small but crucial role in a pivotal event of the war. On September 21, 1780, Peterson, along with Moses Sherwood, brought a cannon from Fort Lafayette at Verplanck’s Point to Croton Point. There they fired on the British frigate “Vulture” which was waiting to pick up Major John André, who at the time was plotting with American General Benedict Arnold for the surrender of West Point. The Vulture abandoned its river position, forcing the spy André to move overland on horseback. He was captured in Tarrytown a few days later carrying plans of West Point. André was hanged in the tiny Rockland County hamlet of Tappan on October 2, 1780. Today, the cannon used by the patriots sits in front of the Peekskill Museum. Sherwood is buried in Ossining’s Sparta Cemetery.

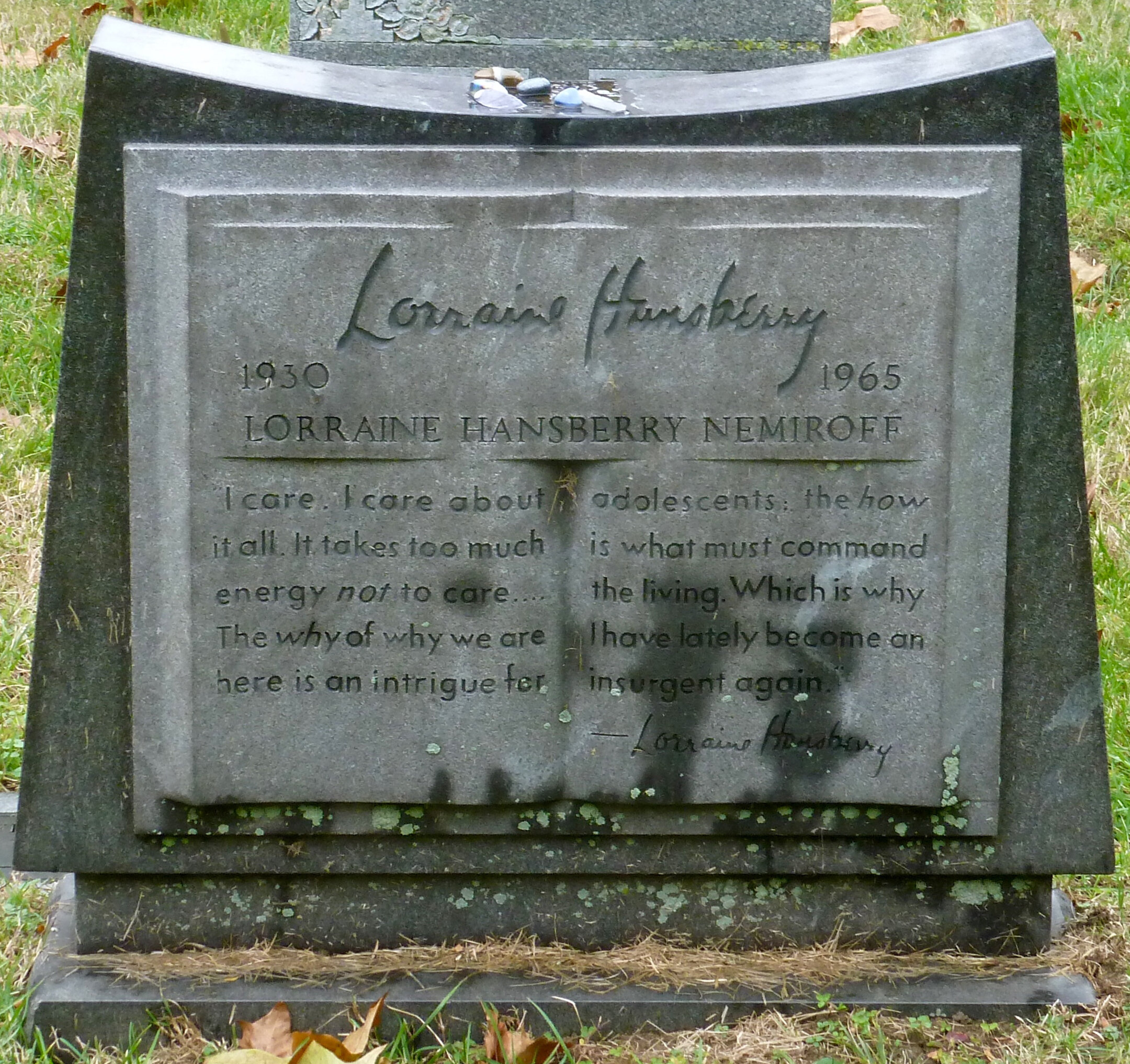

Lorraine Hansberry was an African-American playwright and author of political speeches, letters and essays. Her best known work, A Raisin in the Sun, was inspired by her family’s legal battle against racially segregated housing laws in Chicago during her childhood. It was the first play written by an African-American woman to be produced on Broadway in 1959.

This is the gravestone of John Byron Goldsborough, who moved to Croton in 1895 to supervise the construction of the New Croton Dam.

Modern technology now allows monuments to be shaped, quite literally, into any form you can envision.

Techniques such as sandblasting, shape carving, laser and hand etching now allow intricate scenes and portraits to be placed onto the stone.

Much depends upon the layout of the graveyard. If there were a church-chapel in the center of the cemetery on high ground, the location of access roads was important. Early graves were seldom in the neat rows that we are used to seeing today. Burials were more haphazard and irregular. With the coming of the Rural Cemetery Movement in the 1830s-1840s, an entirely new style of burial became popular. The ideal of winding roads and irregular terrain dictated the orientation of the monuments to a large degree.

American grave markers reveal the past of our community and country. From these stone artifacts we can learn about local residents whose lives were documented at the time, inscribed by carvers who were their neighbors in the village. Names of the famous, the infamous, and ordinary men, women and children were permanently recorded for posterity. At the same time an exciting parallel event occurred—American gave birth to its very first folk art in the form of these graven images.

Unusual for an old Colonial burial ground, Bethel is located in the midst of the Village where it is a familiar everyday scene for local passers-by, part of the streetscape. Although it was founded by Methodists, one need not be Methodist to be buried in Bethel. The cemetery’s non-demoninational flavor has remained throughout time and is a symbol of the special inclusive feeling that makes the community unique.