A Bridge Goes to Court

By Carl Oechsner

Edited by Gretchen Bock

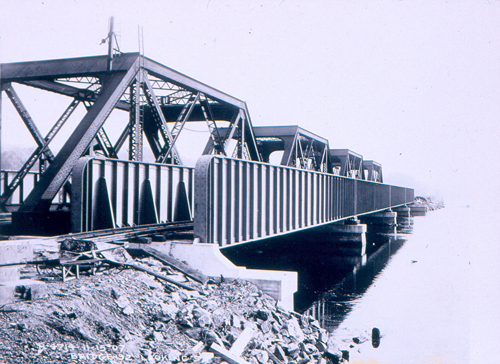

Four section steel bridge carrying four tracks across the Croton River.

Four section steel bridge carrying four tracks across the Croton River.

Crossing the Croton River, a simply styled metal bridge carries local area commuters and also long distance travelers. Both Amtrak and Metro North railroad lines cross this overpass on the way to New York City and to upstate New York. The bridge is taken for granted by most train passengers, who only notice the structure when they hear rumbling beneath their feet. This bridge, however, has an interesting twist because in 1929 it was the subject of a five-year lawsuit involving the railroad and a historic local family living nearby.

New York Central Railroad drawbridge on the Harlem River, ca. 1860.

New York Central Railroad drawbridge on the Harlem River, ca. 1860.

Our story begins in 1846 when the Hudson River Railroad was chartered to build a rail line from New York City to Albany. The rail company was authorized to erect a bridge over all navigable streams or inlets. Every bridge had to be well constructed and have a “draw” to admit the passage of vessels with standing masts into rivers, streams, bays or inlets. If any dock or wharf were cut off by a new bridge, the dock or wharf had to be restored to its former usefulness.

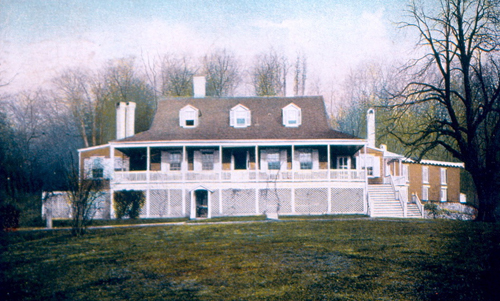

Van Cortlandt Manor House

Van Cortlandt Manor House

The Croton River railroad bridge was built on land that was part of the original Van Cortlandt Manor. That land had been granted by royal charter to Stephanus Van Cortlandt in 1697 and had been owned by his family ever since. In 1847 Pierre Van Cortlandt sold land and water rights to the railroad and the bridge was constructed. For many years afterward the Croton River was used for navigation. Mills and factories lined its banks and sailing vessels passed through the drawbridge.

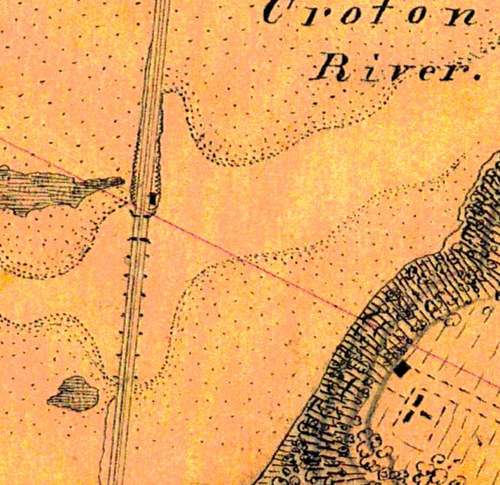

Hudson River Railroad drawbridge, 1854, Croton Point to the left.

Hudson River Railroad drawbridge, 1854, Croton Point to the left.

By 1891, however, everything had changed. Factories and mills had been demolished; river traffic had virtually ceased. The railroad company had consistently maintained two tracks and an open draw on the bridge up to this point, but in 1891 the draw section—no longer needed, just an inconvenience—was dismantled and became a non-movable structure. Freight and passenger service on the rail line was booming and in 1907 two additional tracks were laid. In 1929 trains passed over the bridge at an average of one every three minutes and carried five million passengers and five million tons of freight. Immediately north of the bridge was the Harmon Station, along with shops and yards for locomotive repair and storage.

Closeup of Croton River drawbridge, 1854

Closeup of Croton River drawbridge, 1854

The Van Cortlandts still owned 153 acres of land east of the railroad tracks. The Croton River ran through their property up to the Albany Post Road (Route 9 today), which crossed the river on a masonry arch bridge erected 1922-1924 by Westchester County and the State of New York. In 1929 the family brought legal action to obtain a judgment declaring the rigid, immovable railroad bridge over the Croton River an “unlawful obstruction and a public nuisance” and requesting its removal.

Postcard of Hudson River Railroad drawbridge, ca. 1880.

Postcard of Hudson River Railroad drawbridge, ca. 1880.

A precedent decision had been passed down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1897 involving a similar bridge issue in Louisiana, Egan v. Hart. The Court ruled that states may improve their transportation routes as they see fit, including erecting bridges without draws over navigable streams, unless Congress were to pass an act against the practice.

Harmon shops being built in 1907.

Harmon shops being built in 1907.

The Van Cortlandts did not claim that the Croton was navigable east of the Albany Post Road since there was then no possibility of any commercial navigation on the river beyond the Albany Post Road. Nor did they argue that the Albany Post Road, in shutting off navigation, was an illegal “public nuisance”. A major point they made was that the portion of their property which ran from the railroad bridge to the Albany Post Road crossing would be far more valuable if there were the “possibility of a future use by dredging and bulk heading, and an open draw thru which boats might perhaps come when such work is complete.” They also argued that “at present [1929] the Croton River cannot be used for commerce.”

Albany Post Road bridge built in 1924 across the Croton River.

Albany Post Road bridge built in 1924 across the Croton River.

Attorneys for the railroad pointed out that before 1891 the span across the Croton River could be elevated and swung to one side to admit boats. Testimony pointed out: “No boat has sought to go in or out for over 40 years. No one has had the occasion to use the railroad bridge draw, there was no place to go, no commerce, no business of any kind, no user of adjoining property requiring or demanding navigation, even were navigation possible.”

Rendering of successive designs for an evolving railroad bridge.

Rendering of successive designs for an evolving railroad bridge.Railroad defense focused on the fact that the Van Cortlandt family never intended to use the river channel for boats of any kind. Attorneys argued that not one person from the family ever came forward to say that they desired to use the river for commerce. Had they done so, they would not have been prevented from using it.

1880 William Miller painting of Croton River with Van Cortlandt Manor to the left.

1880 William Miller painting of Croton River with Van Cortlandt Manor to the left.

The river had been abandoned for navigation; mills and factories formerly on its shores, demolished. The first Croton Dam had clogged its upper waters in 1841 and a drift in its currents had caused sand and mud to collect, narrowing its channel.

The railroad bridge in 1913 looking toward Harmon Station from Ossining

The railroad bridge in 1913 looking toward Harmon Station from Ossining

With the opening of the New Croton Dam and reservoir expansion in 1907—which made less water available in the lower Croton River—and the completion by New York State of a new bridge on Route 9 (former Albany Post Road) in 1924, there was no longer a navigable channel available from the railroad bridge to the Route 9 span.

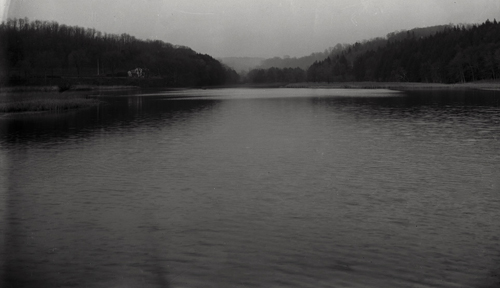

Croton River in 1925 with Van Cortlandt Manor to the left.

Croton River in 1925 with Van Cortlandt Manor to the left.

The trial court in White Plains heard the case with this overview: “The Van Cortlandt family have sought to obtain judgment declaring the rigid and immovable railroad bridge of the New York Central Railroad over the Croton River to be an unlawful obstruction and public nuisance, and further directing its removal.” The court dismissed the complaint on the grounds that the Croton River was non-navigable and that the Van Cortlandts were guilty of an unreasonable delay in failing to make any move or objection for a period of over 40 years.

Albany Post Road bridge, 1924.

Albany Post Road bridge, 1924.

The Appellate Division Court reversed many of the findings and conclusions of the lower court and the case moved to the Court of Appeals in Albany. That Court concluded that the State of New York had the power to improve its transportation routes as it deemed best for travel, even to the extent of erecting bridges without draws over navigable streams.

1950 photo of present-day Metro-North Railroad bridge.

1950 photo of present-day Metro-North Railroad bridge.

It also ruled: “It must not be forgotten that bridges, which are connecting parts of turnpikes, streets and railroads, are means of commercial transportation, as well as [are] navigable waters, and that the commerce which passes over a bridge [as do New York Central Railroad and Route 9] may be much greater than would ever be transported on the water the bridge obstructs.”

Aerial view of the Metro-North Bridge (lower right) looking up the mouth of the Croton River.

Aerial view of the Metro-North Bridge (lower right) looking up the mouth of the Croton River.

The Court also concluded: “The railroad had the right to place a bridge over the Croton River in 1846, but there is very grave doubt whether there was any intent to have such a provision apply to a remaining bit of the original stream shut off by a highway in 1924 some 2,400 feet beyond the railroad crossing, unused for over 40 years and of no commercial value at present.”

The bridge presently serves Metro-North Hudson Line, Amtrak, and CSX Transportation.

The bridge presently serves Metro-North Hudson Line, Amtrak, and CSX Transportation.

On October 2, 1934, the New York State Court of Appeals ruled unanimously that the Van Cortlandts had failed to prove sufficient damage to their property, that the decision by the lower Appellate Division courts was reversed, and that the complaint was dismissed.